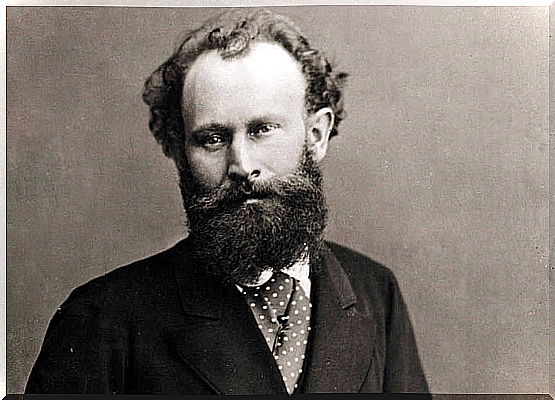

Édouard Manet, Biography Of The First Impressionist

Édouard Manet was a French painter of the s. XIX that served as inspiration for many other later painters thanks to his style and way of representing. Manet broke new ground by challenging traditional techniques of representation by choosing to paint the events and circumstances of his time.

His painting Déjeuner sur l’herbe (Lunch on the Grass), exhibited in 1863 in the Hall of the Rejected, aroused hostility from critics. Although, simultaneously, he received the applause and enthusiasm of a new generation of painters who, later, would form the nucleus of the Impressionist movement.

Early life

Édouard Manet was born on January 23, 1832, in Paris, France. He was the son of Auguste Manet, a senior official in the Ministry of Justice. His mother, Eugénie-Désirée Fournier, was the daughter of a diplomat and the goddaughter of the Swedish crown prince.

Wealthy and with a number of influential contacts, the couple hoped their son would choose a respectable career and, as a preference, law. However, the future held a humanistic career for Manet.

From 1839, he was a pupil at Canon Poiloup’s school in Vaugirard. From 1844 to 1848, he remained an intern at the Collège Rollin. He was a poor student, interested only in the special drawing course offered by the school.

Despite the fact that his father wanted him to enroll in law school, Édouard did not decide this fate. When his father refused to allow him to become a painter, he applied to the naval college, but failed the entrance exam.

At age 16, he embarked as an apprentice pilot on a transport ship. Upon his return to France in June 1849, he failed the naval examination for the second time, and his parents finally gave in to their son’s stubborn determination to become a painter.

Manet’s first formal studies

In 1850, Manet entered the studio of the classical painter Thomas Couture. There, he developed his good understanding of drawing and painting technique.

In 1856, after six years with Couture, Manet established a studio that he shared with Albert de Balleroy, a painter of military subjects. There he painted The Boy with Cherries (1858) before moving to another studio where he would paint The Absinthe Drinker (1859).

In the same year, he made short trips to the Netherlands, Germany, and Italy. Meanwhile, in the Louvre he copied paintings by Titian and Diego Velázquez.

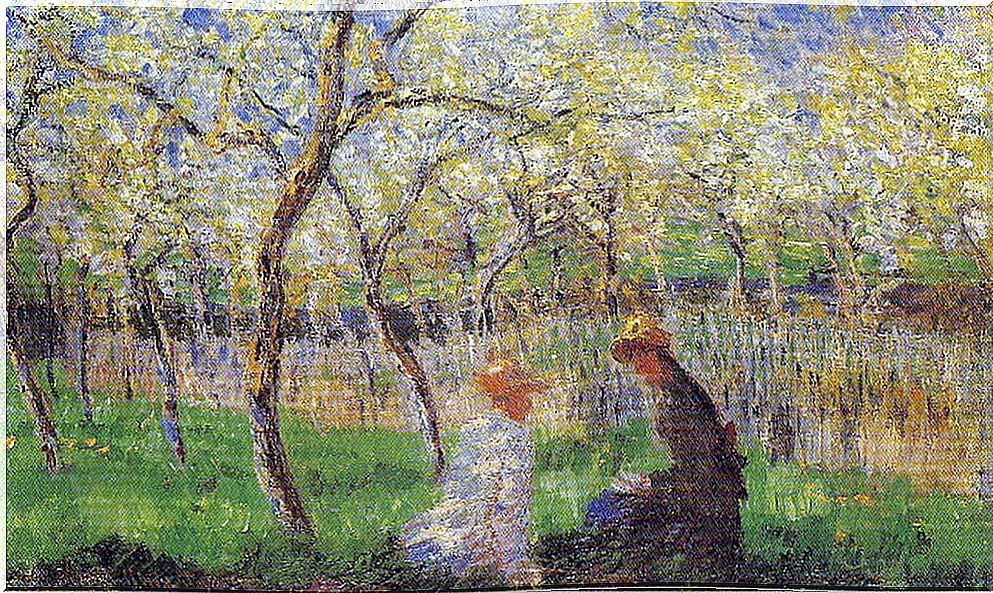

Despite his success with realism, Manet began to approach a more relaxed and impressionistic style; characterized by the use of broad brushstrokes and the incorporation in his paintings of ordinary people who were engaged in daily tasks.

His canvases were filled with singers, street people, gypsies and beggars. This unconventional approach combined with a mature knowledge of the old masters surprised some and impressed others.

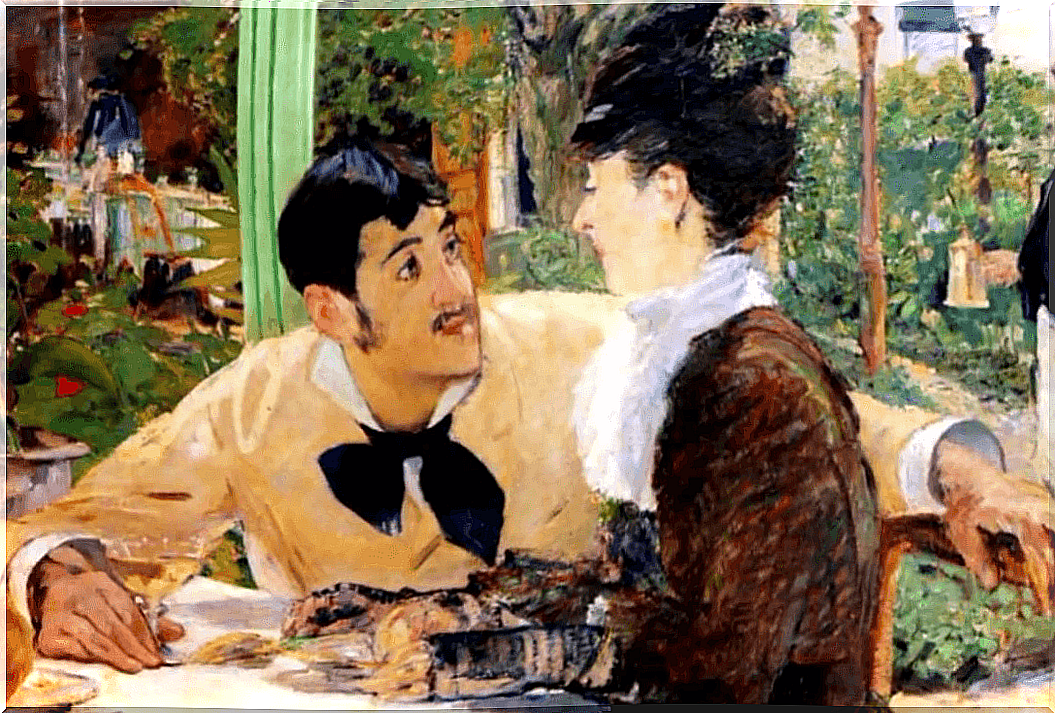

Mature Life and Breakfast on the Grass

Between 1862 and 1865, Manet participated in exhibitions organized by the Martinet Gallery. In 1863, Manet married Suzanne Leenhoff, a Dutch woman who had given him piano lessons. The couple had already been in a relationship for ten years and had a child together before marriage.

That same year, the Salon jury rejected his Breakfast on the Grass , a work whose technique was completely revolutionary. For this reason, Manet exhibited it at the Salon de los Rechazados, founded to showcase the many works rejected by the official Salon de Bellas Artes.

Breakfast on the grass was inspired by works by old masters such as: The Pastoral Concert (Giorgione, 1510) or The Judgment of Paris (Raphael, 1517-20). This large canvas caused great disapproval and began for Manet the ‘carnival notoriety’ for which he would suffer for most of his career.

His critics were offended by the presence of a naked woman in the company of two young men dressed in contemporary clothes. Thus, instead of looking like a remote allegorical figure, the woman’s modernity made her nakedness seem vulgar and even threatening.

Critics were also upset by the way these figures were rendered in harsh, impersonal light. Furthermore, they did not understand why the figures were set in a forest setting whose perspective is clearly unrealistic.

Main works

In the 1865 salon, his Olympia painting , created two years later, caused another scandal. The reclining nude woman in the painting looks unabashedly at the viewer and is depicted in a harsh, brilliant light that erases the interior modeling and turns her into an almost two-dimensional figure.

This contemporary odalisque, which the French statesman Georges Clemenceau was to install in the Louvre in 1907, was described as indecent by critics and the public.

In his affliction, Manet set out in August 1865 for Spain. However, his stay in Spain was short, as he did not like food and was frustrated by his total lack of knowledge of the language.

In Madrid, he met Théodore Duret, who would later become one of the first connoisseurs and defenders of his work. In 1866, he came into contact and befriended the novelist Emile Zola who, in 1867, wrote a brilliant article on Manet in the French newspaper Figaro .

Zola pointed out how almost every major artist begins by offending the public’s sensibilities. This review impressed the art critic Louis-Edmond Duranty, who also began to support him. Painters like Cézanne, Gauguin, Degas, and Monet became his allies.

Later years

In 1874, Manet was invited to exhibit at the first exhibition held by Impressionist artists. Despite his support for the movement, he rejected the invitation and the subsequent ones that would come from the Impressionists.

Manet felt it necessary to remain dedicated to the salon and its place in the art world. Like many of his paintings, Édouard Manet was a contradiction, being at the same time bourgeois and common, conventional and radical.

A year after the first Impressionist exhibition, he was offered the opportunity to draw illustrations for the French edition of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven . In 1881, the French government granted him the Légion d’honneur.

He died two years later in Paris, on April 30, 1883. In addition to 420 paintings, he left a reputation that would forever define him as a bold and influential artist.

Legacy

Manet’s debut as a painter met critical resistance that did not diminish until near the end of his career.

Its profile was raised at the end of the 19th century, thanks to the success of its commemorative exhibition and the eventual critical acceptance of the Impressionists. But it wasn’t until the 20th century that art historians assured him of his reputation.

Manet’s disregard for traditional modeling and perspective marked the break of the s. XIX with academic painting. His work undoubtedly paved the way for the revolutionary work of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists.

Manet, in turn, influenced much of the art of the 19th and 20th centuries through his choice of subjects. His focus on modern urban themes, which he presented directly, almost distantly, further distinguished him from the Hall’s standards.